So what is capitalization about? And what would a social inquiry into capitalization look like? In a recent post, it was suggested that a social inquiry into capitalization requires “understanding capital not as a thing in itself — something that one has or has not — but rather as a form of action, a form of grip, a form of power, an act of configuration, an operation, a situation”. Where such an inquiry can draw inspiration from? Karl Marx’s analysis of capital as a “social relation” appears as an obvious place to start with.

In a chapter of Capital entitled “The Modern Theory of Colonisation”, Marx took up the story of Thomas Peel, a colonial promoter and early settler at Swan River, whose misfortunate venture had earlier been described by Edward Gibbon Wakefield in his book England and America (1833):

“Mr. Peel, [Wakefield] moans, took with him from England to Swan River, West Australia, means of subsistence and of production to the amount of £50,000. Mr. Peel had the foresight to bring with him, besides, 300 persons of the working class, men, women, and children. Once arrived at his destination, “Mr. Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river.”” (Marx, Capital, chapter XXXIII)

Wakefield had used Mr. Peel’s story to develop his theory of “systematic colonization”, arguing in particular that the price of land should be made high enough to ensure the availability of labour — otherwise, the labourers whom capitalists brought with them to the new settlements would do as those who came with Mr. Peel did: leave, to find their own piece of land. Marx, instead, used Mr. Peel’s story to depict capital as a social relation, rather than “a thing”. Mr. Peel’s problem, Marx wrote, was that he had “provided for everything except the export of English modes of production to Swan River”. And Wakefield’s real finding, Marx claimed, did not have to do with colonies and their management, but with the nature of capital: what Wakefield discovered, through Mr. Peel’s story, was that capital “is not a thing, but a social relation between persons [the capitalist and the wage-worker], established by the instrumentality of things”.

Marx reiterated this point in a chapter of Wage Labour and Capital entitled “The Nature and Growth of Capital”:

“Capital consists of raw materials, instruments of labour, and means of subsistence of all kinds, which are employed in producing new raw materials, new instruments, and new means of subsistence. All these components of capital are created by labour, products of labour, accumulated labour. Accumulated labour that serves as a means to new production is capital.

So say the economists.

What is a Negro slave? A man of the black race. The one explanation is worthy of the other.

A Negro is a Negro. Only under certain conditions does he become a slave. A cotton-spinning machine is a machine for spinning cotton. Only under certain conditions does it become capital. Torn away from these conditions, it is as little capital as gold is itself money, or sugar is the price of sugar.” (Marx, Wage Labour and Capital, chapter 5)

It is precisely in this process through which something “becomes capital” — i.e., capitalization — that we are interested. And there are two insights that we can draw from here. The first one has to do with conditions. For Marx, things become capital “only under certain conditions”, and these conditions are of a socio-material texture, they are made of “social relations … established by the instrumentality of things”. Studying the capitalization of a molecule today, for example, would entail describing the encounter between an investor and a scientist-entrepreneur and their interactions mediated by tools like business plans, Powerpoint presentations and valuation formulae. The second insight has to do with consequences. For Marx, while things become capital, “they serve at the same time as means of exploitation and subjection of the labourer” (Capital, chapter XXXIII). In a certainly less critical take, turning molecules into capital, to continue the example, goes hand in hand with turning scientists into entrepreneurs. A social inquiry into capitalization would thus involve an exploration of the kinds of objects and subjects that are produced in the contemporary settings of capitalization.

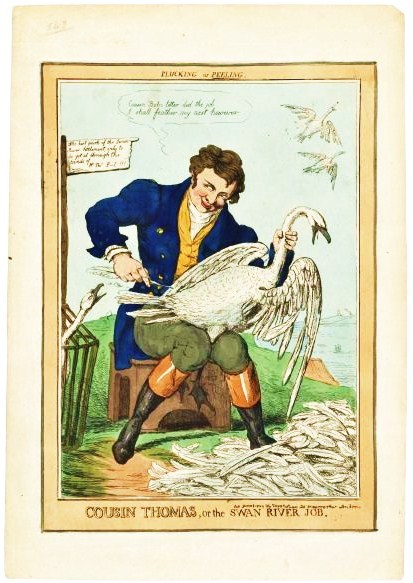

‘Cousin Thomas, or the Swan River Job’, an 1829 caricature of Thomas Peel by Robert Seymour. Source: National Library of Australia.

Thomas is exclaiming “Cousin Bob’s letter did the job I shall feather my nest however.”

On the left is a sign post “The best parts of the Swan River Settlement only to be got at through the hands of Mr. Thos P–l!!”